Among all the types of merchants that accept card transactions, coffee shops, pizza parlors, burger places, and food stores might need to keep an extra careful watch on their card data.

If they're operating as a franchisee and part of a chain, they might want to be especially wary. And if they use a third-party service for system support and maintenance, they'd be well-advised to take even more steps to secure their customers' information.

Call it the trifecta of data-breach vulnerability. But it's not one you want to win.

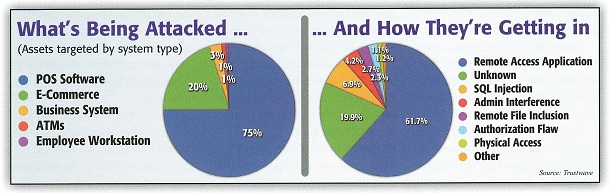

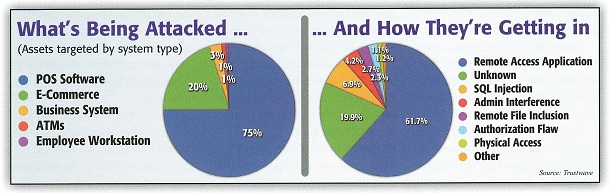

That's because the food-and beverage category was especially vulnerable to breaches in 2011, accounting for nearly 44% of the more than 300 data compromises investigated by Trustwave Holdings Inc., a Chicago based supplier of security technology.

This was the second straight year that the category accounted for the highest number of cases, according to Trustwave, whose SpiderLabs unit investigates breach incidents around the world. About 45% of all of the cases investigated last year were in North America, says Nicholas J. Percoco, head of SpiderLabs and a senior vice president at Trustwave, which last month released its 2012 Global Security Report.

But if you're a franchisee, you really need to watch out. Cybercriminals tended to target franchise operations' which accounted for more than one-third of the cases, according to the report. Outlets that are part of a chain store model are similarly vulnerable.

And if you rely on third parties for IT help, you've invited even more trouble. Stores that depend on outside help to update and maintain their point-of-sale systems were also more likely to sustain a breach. More than three-quarters of the investigations found that a third-party outfit responsible for system support or development had, wittingly or not, introduced the vulnerability.

The good news is that law enforcement authorities appear to be increasingly effective in detecting breaches. They discovered one-third of the cases Trustwave examined, up from only 7% in 2010. Tempering that positive news, however, is that self detected cases fell from 20% to 16%.

That's bad news, says Percoco, because self detection usually occurs much earlier in the duration of a breach, limiting the damage. Hackers were discovered, on average, fully 173.5 days after infiltrating the system in cases where the breach was detected by an outside entity, but in cases of self-detection that was cut to 43 days.

While police and other outside entities may be more on the ball, "unfortunately that's a little too late for some of these merchants," Percoco says.

Franchises and chains tend to be especially vulnerable because they typically rely on common systems imposed on them by a franchisor or other central corporate authority, Percoco says. If these systems are misconfigured, criminals can replicate their attacks at multiple locations once they've spent some time at the first one.

They are patient, too, sometimes spending as many as several months in one location before propagating their attacks with cookie-cutter efficiency. "They'll invest time upfront and then stamp out as many attacks as possible," says Percoco.

It doesn't take much to undermine the security of a system. In many cases, Trustwave found that passwords and user names used to log into systems were "pitifully simple," according to the report. In fact, "Password1" was found to be a common password in actual use. Not surprisingly, what the report calls "use of weak administrative credentials" accounted for 80% of attack propagations.

Often, compliance with industry standards might have prevented the breach or limited the damage. Indeed, in none of the cases Trustwave investigated was the victim compliant with the Payment Card Industry data-security standard (PCI), Percoco says.

Yet, the remedies were in plain sight. "Many of the issues we identified were clearly defined in PCI," he notes